DEFINICIÓN Y FORMACIÓN DE LAS RAZAS BOVINAS

Bavera, G. A. 2000. Curso de Producción Bovina de Carne, FAV UNRC.

www.produccion-animal.com.ar o www.produccionbovina.com

DEFINICIÓN

Una raza es "un grupo segregado de la población que por sus características morfológicas y fisiológicas de-muestran poseer un origen común, cuyo exterior y producción media lo distinguen de los demás grupos de la misma especie, y que transmiten esos caracteres a su descendencia". Es importante comprender bien esta definición para poder diferenciar sin dudar a una raza de una cruza o a una raza obtenida por cruzamientos de una simple cruza.

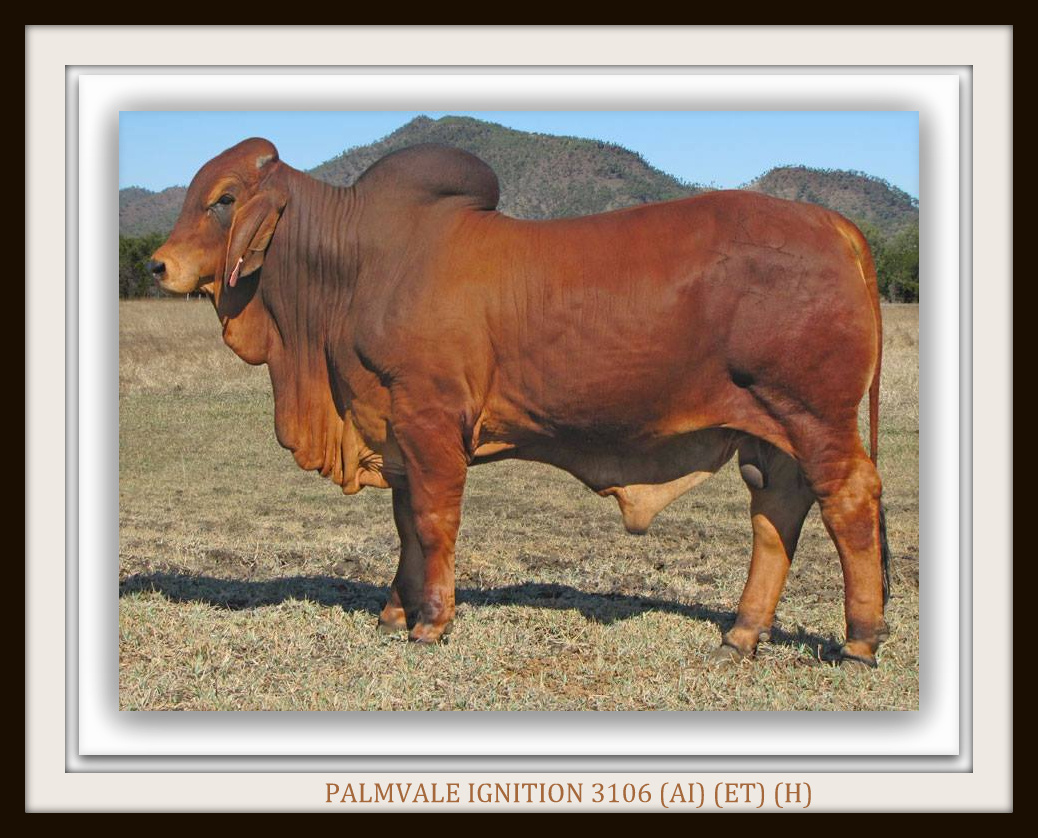

El complejo de caracteres morfológicos y fisiológicos típicos de una raza se conoce como tipo racial. Los caracteres étnicos morfológicos son: piel, pelo, color de las mucosas visibles, cuernos, musculatura, ubre, giba, prepucio, etc. Los caracteres étnicos fisiológicos son: temperamento, producción de leche, grasa butiro métrica, glóbulos grasos de la leche, color de la leche, peso vivo, veteado, rinde, fertilidad, facilidad al parto, adaptación, resistencia a enfermedades, aptitud materna, aumento diario de peso, conversión alimenticia, etc.

Es posible producir una raza que sea homocigota para uno o varios caracteres morfológicos, aunque como norma esto no servirá para distinguirla de las restantes razas, ya que diversas razas pueden poseer idénticas características externas. Además, estas características raciales morfológicas poseen una importancia reducida en los bovinos.

Los aspectos de la producción, que determinan la importancia económica de la raza, muestran una variación constante, y no puede establecerse una línea divisoria clara entre las razas, aún cuando los promedios raciales muestran divergencias bastante amplias. Estas características se ven sometidas a la influencia de un gran número de genes, y se aprecia en todas las razas un amplio grado de heterocigosis en relación con todos los aspectos cuantitativos. En consecuencia, y hablando en sentido biológico, no ganadero, no existen razas puras de animales domésticos.

Cuando se emplean en la práctica los términos raza pura o puro de peligre, se refiere a los animales que han sido registrados en el libro genealógico de la raza (HB). Estos animales de raza pura constituyen un grupo se-lecto que se destina a la reproducción. Los requisitos que se exigen para que se acepte un animal en el libro genea-lógico varían con la época y el lugar, y los fija la respectiva asociación de criadores. En la ganadería práctica el concepto de raza es convencional mas que biológico. Sin embargo, la división en razas está justificada porque las poblaciones que componen las razas se han especializado para fines diferentes y adaptado a distintas condiciones ambientales.

En la actualidad, el único valor que puede tener el pedigrí es el de brindar una guía para evaluar el valor zoo-técnico del animal al cual pertenece. Si el animal es sometido a una prueba de progenie, entonces el pedigrí es superfluo.

LA OBRA DE BAKEWELL

El uso del peligre comenzó en el ámbito rural de Inglaterra hacia fines del siglo XVIII, y la formación de las primeras sociedades de registro de razas se inició alrededor de la mitad del siglo XIX. A Roberto Bakewell se le atribuye el mérito de haber creado el esquema de la moderna cría animal. Su mayor éxito personal reside en haber sabido popularizarla mas de lo que pudo hacer el esfuerzo de cualquier otro hombre individualmente.

Roberto Bakewell (1725-1795) era un granjero inglés. En 1760 se hace cargo de su propiedad en Dishley. Fue un buen granjero, además de descollar en la cría animal. Tuvo destacada participación en la introducción de nabos y otros cultivos en la agricultura inglesa. Buen observador, estudioso de la anatomía y buen juez de ganado, guar-daba para futuras referencias huesos y articulaciones conservadas en salmuera de animales que había criado y consideraba casi ideales. Contaba poco acerca de sus prácticas, a tal punto que muchos de sus contemporáneos pensaban que hacía algo misterioso de ellas. Se cree que lo hacía deliberadamente para evitar la competencia o la censura. Un elemento importante en sus procedimientos era la intensa endocría, y en aquella época había un gran pre-juicio sobre los apareamientos consanguíneos en animales, a los que mucha gente lo consideraba casi un sacrilegio.

La cría a que se dedicaba Bakewell fue el antiguo ganado Longhorn, la oveja Leicester y los caballos Shire. Logró tan resonantes éxitos que sus animales tuvieron gran demanda como reproductores. Inauguró la práctica del arrendamiento de reproductores. Esto es, no vendía sus mejores animales, sino que los alquilaba por un año. Sus subastas anuales o arrendamientos despertaban gran interés y lograba envidiables éxitos financieros. Mediante

2

esta práctica de arrendamiento, los mejores reproductores retornaban a sus rodeos todos los años, y los ejemplares cuya progenie demostraba que eran superiores a los demás, los mantenía para el uso de sus propios rodeos.

El éxito de Bakewell atrajo a numerosos ganaderos, que de muchas partes de Gran Bretaña fueron a Dishley a estudiar sus métodos. Algunos se quedaron hasta seis meses, y a su regreso aplicaron sus métodos al ganado que habían adquirido en Dishley o al que consideraban como el mejor de sus propios planteles. Los Colling, que sentaron los cimientos de la raza Shorthorn, mantenían estrechos vínculos con Bakewell, y también lo hicieron criadores de Hereford y Aberdeen Angus. Tantos eran sus seguidores que habían logrado destacados éxitos, que a lo largo de toda Inglaterra no tardaron en formarse planteles de animales emparentados de cerca y de tipo similar. De estos planteles se originaron luego las razas modernas, la mayoría de las cuales se organizarían formalmente sólo mas tarde.

Lo principios que usó Bakewell incluían premisas aún vigentes tales como: "los semejantes producen semejan-tes o semejanza con algún antecesor; la consanguinidad produce predominio y refinamiento; aparee al mejor con el mejor". Recuérdese que en esta época aún no se habían descubierto las leyes de Mendel.

Su mayor contribución a los métodos de cría radica en su apreciación del hecho de que la cría consanguínea es el método mas efectivo para lograr refinamiento del tipo. Era remiso a hacer cruzamientos con ejemplares extraños cuando sus propios ejemplares le parecían mejor que los de sus vecinos.

Cuando las mejoras logradas por Bakewell y sus seguidores comenzaron a ser conocidas en otras tierras, la ex-portación de animales de cría a aquellos países comenzó a convertirse en fuente de apreciables ingresos para los ganaderos británicos. Ello incitó a nuevas mejoras para asegurarse que los compradores extranjeros volverían en busca de reproductores frescos, y tuvo que ver mucho con la orientación de las sociedades de registro de razas.

FORMACION DE LAS RAZAS ANTIGUAS

Si bien cada raza ha tenido una historia peculiar y circunstancias especiales en su formación, todas las antiguas han seguido un patrón relativamente similar. Este patrón se caracteriza por hechos subsecuentes: aislamiento y consanguinidad por razones geográficas, intervención de criadores que intentan mejorar el tipo local (general-mente por hibridación con otros tipos distantes) y enseguida un nuevo proceso de aislamiento y consanguinidad. A estos intentos siguen los esfuerzos de un conjunto de ganaderos que eventualmente forman una asociación de criadores de la raza. El proceso continúa con la inscripción de animales fundadores en libros genealógicos (HB) y la posterior publicación de nuevos libros con los registros de animales descendientes de los fundadores (puros de peligre) o de los fundadores con otros animales de la raza (puros por cruza). Finalmente, en muchas razas modernas termina el proceso con la formación de registros selectivos que reconocen dentro del pedigrí una elite de animales superiores por encima del concepto de pureza de raza.

El primer paso en la formación de razas, el aislamiento geográfico, es fácil de comprobar en la historia de todas las razas antiguas del viejo continente. Así, el Hereford se originó en la región de Herefordshire, en Inglaterra. El Shorthorn proviene de los primeros ganados del río Tees, en los condados de Durham, York y Lincoln. Se pue-den multiplicar hasta cientos las razas europeas íntimamente ligadas a una región geográfica restringida, hasta casos peculiares de aislamiento. Por ejemplo, Suiza, que posee dos razas notables, que son la Pardo Suiza y la Sim-mental, posee otras razas menores, como la Race d'Herens, completamente distinta a las anteriores y aislada en pequeños valles tributarios del Ródano. Ahí la Race d'Herens forma el 100 % de la población bovina, aunque en toda Suiza no forme sino menos del 1 % .

En otros continentes la relación entre zonas geográficas y tipos o razas también es evidente. Así, en el ganado cebú, la clasificación de razas sigue casi exactamente la de zonas geográficas y hecho similar se encuentra en Á-frica.

El solo aislamiento geográfico (que causa desvíos al azar) puede formar tipos distintivos (a veces muy peculiares, como el caso de la raza West Highland, de Escocia), pero a la producción animal le interesa mas la excelencia económica de las razas que sus peculiaridades excéntricas. Hace falta, además de la base distintiva de origen geo-gráfico, la mano de ciertos criadores que modelen el tipo local para hacerlo más útil al hombre. En todas las razas notables se encuentran en su primera formación un número de criadores con extremada habilidad y visión que perfeccionan los tipos de ganado para hacerlos mas uniformes y productivos. Debe repararse en este requisito de contar con un número de criadores y no con un solo criador. Así ocurre que en la historia ganadera, el hombre mas notable, Robert Bakewell, trabajó sobre tres razas de tres especies que no tuvieron mayor importancia posterior-mente, ya que no se formó un grupo de criadores que continuaran con el perfeccionamiento de dichas razas.

Muchas de las razas más importantes del mundo adquirieron prestigio antes que se organizaran los libros genealógicos y se pensara en los conceptos de pureza de dichas razas. Así, el ganado de Frisia (Holando) era considerado de excelentes cualidades lecheras mucho antes que existieran libros genealógicos o asociaciones de criado-res en Holanda. Es notable que el primer libro genealógico del ganado Holando se creara en EE.UU. y se incluye-ran animales originarios de Holanda, pero sin ningún registro previo en ese país. Algunos de los libros se iniciaron como empresas privadas de individuos que se dedicaban a llevar los apuntes genealógicos de animales en manos

Curso Incompleto de Producción Bovina de Carne

3

de los mas prominentes criadores. En esta forma se inició el primer libro genealógico del mundo (el Coates Herd-book) para la raza Shorthorn o Durham, en 1822, y el libro de Eyton para el Hereford en 1846. Pronto esta responsabilidad fue asumida por las asociaciones de criadores. En algunas ocasiones existieron varios libros pertene-cientes a diferentes asociaciones. Por ejemplo, para el Holstein (Holando) en EE.UU. se formó una asociación de registro en 1871 y otra en 1877. Las asociaciones generalmente se unían, como sucedió con estas en 1885. En otras ocasiones, de un solo registro primitivo se originaron dos nuevos que prosiguieron adelante como represen-tativos de razas diferentes. Esto ocurrió con el libro del ganado Negro Mocho de Escocia, iniciado en 1862, que incluía los ancestros tanto del Aberdeen Angus como del Galloway.

FORMACION DE LAS RAZAS NUEVAS

La explotación de nuevas regiones del mundo o el aumento de la producción en ciertas zonas poco explotadas en el pasado, crearon oportunidades para nuevos tipos de animales. En el siglo XX se ha adelantado mucho en este sentido, con la formación de nuevas razas bovinas: Santa Gertrudis, Indú Brasil, Beefmaster, Brangus, Beefa-lo, etc., creadas para regiones geográficas específicas y con estricta selección sobre su capacidad productiva.

En la formación de todas estas nuevas razas, el proceso ha tenido algunos aspectos similares, basado en el cruzamiento:

1) Cruzamiento de una raza o línea consanguínea que posea cualidades deseables con otra raza o línea consanguínea que posea otras cualidades deseables diferentes. Téngase en cuenta que en este siglo la genética ya es una ciencia, y en la formación de estas razas actuaron genetistas y no solo ganaderos.

2) Exploración de las recombinaciones posibles entre las dos líneas, conservando los individuos que más se acercan al ideal deseado. Aquí se utiliza la segregación que ocurre en F2 y F3 o bien retro cruzas a una de las razas, procurando que los animales que entran en la retro cruza lleven algunas de las cualidades que la raza original no posee.

3) Selección estricta de los individuos fundadores y aumento consecuente de la consanguinidad y uniformidad de los núcleos fundadores.

4) Expansión del número de individuos de la nueva raza y del número de criadores dedicados a ella. Reducción del ritmo de aumento de consanguinidad y de la presión de selección en manos menos hábiles que la de los primeros criadores de la raza.

DEFINITION

A race is "a segregated group of the population that, due to its morphological and physiological characteristics, shows that it has a common origin, whose exterior and average production distinguish it from other groups of the same species, and that transmit these characters to their offspring" . It is important to understand this definition well to be able to differentiate without hesitation a breed from a cross or a breed obtained by crosses from a simple cross.

The complex of morphological and physiological characters typical of a breed is known as a racial type. The ethnic morphological characters are: skin, hair, color of the visible mucous membranes, horns, muscles, udder, hump, foreskin, etc. The ethnic physiological characters are: temperament, milk production, butyro-metric fat, milk fat globules, milk color, live weight, marbling, yield, fertility, calving ease, adaptation, resistance to diseases, maternal aptitude, increase weight diary, feed conversion, etc.

It is possible to produce a race that is homozygous for one or more morphological characters, although as a rule this will not serve to distinguish it from other races, since different races can have identical external characteristics. Furthermore, these racial morphological characteristics are of reduced importance in bovines.

Aspects of production, which determine the economic importance of the breed, show constant variation, and no clear dividing line can be established between the breeds, even though the racial averages show fairly wide divergences. These characteristics are subject to the influence of a large number of genes, and a wide degree of heterozygosity is seen in all races in relation to all quantitative aspects. Consequently, and speaking in a biological, non-livestock sense, there are no pure breeds of domestic animals.

When the terms pure breed or pure endangered breed are used in practice, it refers to animals that have been registered in the breed studbook (HB). These purebred animals constitute a select group that is destined for reproduction. The requirements for an animal to be accepted in the herd book vary with time and place, and are set by the respective breeders' association. In practical farming the concept of breed is conventional rather than biological. However, the division into races is justified because the populations that make up the races have specialized for different purposes and adapted to different environmental conditions.

At present, the only value that the pedigree can have is to provide a guide to assess the zoo-technical value of the animal to which it belongs. If the animal is subjected to progeny testing, then the pedigree is superfluous.

THE WORK OF BAKEWELL

The use of the hazard began in rural England towards the end of the 18th century, and the formation of the first breed registration societies began around the middle of the 19th century. Robert Bakewell is credited with creating the blueprint for modern animal husbandry. His greatest personal success lies in having known how to popularize her more than the effort of any other man individually could.

Robert Bakewell (1725-1795) was an English farmer. In 1760 he took over his property in Dishley. He was a good farmer, as well as excelled in animal husbandry. He had an outstanding participation in the introduction of turnips and other crops in English agriculture. A good observer, a student of anatomy and a good judge of cattle, he kept for future reference bones and joints preserved in brine from animals that he had raised and considered almost ideal. He said little about his practices, to the point that many of his contemporaries thought he was doing something mysterious about them. It is believed that he did so deliberately to avoid competition or censorship. An important element in their procedures was the intense inbreeding, and at that time there was a great prejudice about the consanguineous matings in animals, which many people considered almost a sacrilege.

Bakewell's breeding stock was ancient Longhorn cattle, Leicester sheep, and Shire horses. He achieved such resounding success that his animals were in great demand as breeders. He inaugurated the practice of reproducing leasing. That is, he did not sell his best animals, but rented them for a year. His annual auctions or leases aroused great interest and achieved enviable financial success. Through

2

In this leasing practice, the best breeders returned to his herds every year, and the specimens whose progeny proved to be superior to the others, she kept for the use of her own herds.

Bakewell's success attracted numerous ranchers, who from many parts of Britain came to Dishley to study his methods.

Some stayed up to six months, and upon their return they applied their methods to cattle they had acquired from Dishley or to what they considered the best of their own stock. The Collings, who laid the foundations of the Shorthorn breed, had close ties to Bakewell, and so did Hereford and Aberdeen Angus breeders. So many were his followers who had achieved remarkable success, that throughout England it was not long before herds of closely related animals of similar type were formed. From these establishments the modern races later originated, most of which would be formally organized only later.

The principles that Bakewell used included still valid premises such as: "the like produce resemblances or resemblance to some ancestor; consanguinity produces dominance and refinement; pair the best with the best." Remember that at this time Mendel's laws had not yet been discovered.

His greatest contribution to breeding methods lies in his appreciation of the fact that inbred breeding is the most effective method for achieving type refinement. He was reluctant to cross strange specimens when his own specimens seemed better to him than those of his neighbors.

When the improvements achieved by Bakewell and his followers began to be known in other lands, the export of livestock to those countries began to become a source of considerable income for British cattlemen. This prompted further improvements to ensure that foreign buyers would return for fresh breeders, and had a lot to do with the orientation of breed registration societies.

FORMATION OF THE ANCIENT RACES

Although each race has had a peculiar history and special circumstances in its formation, all the ancient ones have followed a relatively similar pattern. This pattern is characterized by subsequent events: isolation and consanguinity for geographic reasons, the intervention of breeders who try to improve the local type (generally by hybridization with other distant types), and then a new process of isolation and consanguinity. These attempts are followed by the efforts of a group of breeders who eventually form an association of breeders of the breed. The process continues with the registration of founding animals in herd books (HB) and the subsequent publication of new books with the records of animals descended from the founders (pure dangerre) or of the founders with other animals of the breed (pure by cross ). Finally, in many modern breeds the process ends with the formation of selective registries that recognize within the pedigree an elite of superior animals over and above the concept of breed purity.

The first step in the formation of races, geographic isolation, is easy to verify in the history of all the ancient races of the old continent. Thus, the Hereford originated in the Herefordshire region of England. The Shorthorn comes from the first cattle of the River Tees, in the counties of Durham, York and Lincoln. The European races closely linked to a restricted geographical region can be multiplied up to hundreds, up to peculiar cases of isolation. For example, Switzerland, which has two notable races, which are the Brown Swiss and the Sim-mental, has other minor races, such as the Race d'Herens, completely different from the previous ones and isolated in small tributary valleys of the Rhone. There the Race d'Herens forms 100% of the bovine population, although throughout Switzerland it forms only less than 1%.

In other continents the relationship between geographical areas and types or races is also evident. Thus, in zebu cattle, the breed classification follows almost exactly that of geographical areas and a similar fact is found in Africa.

Geographical isolation alone (causing random deviations) can form distinctive types (sometimes very peculiar, as in the case of the West Highland breed from Scotland), but animal production is more interested in the economic excellence of the breeds than their eccentric peculiarities. It is necessary, in addition to the distinctive base of geo-graphic origin, the hand of certain breeders who model the local type to make it more useful to man. In all the notable breeds, a number of breeders with extreme skill and vision are found in their early training who perfect the types of cattle to make them more uniform and productive. This requirement of having a number of breeders and not a single breeder should be noted. Thus it happens that in livestock history, the most remarkable man, Robert Bakewell, worked on three races of three species that did not have greater importance later, since a group of breeders was not formed to continue with the improvement of these races.

Many of the world's leading breeds gained prestige before herd books were organized

and the concepts of purity of said races will be thought about. Thus, Frisian (Holando) cattle were considered to be of excellent dairy qualities long before there were herd books or breeder associations in Holland. It is notable that the first Holando cattle herd book was created in the US and included animals originating in the Netherlands, but without any prior registration in that country. Some of the books were started as private companies of individuals who were dedicated to keeping the genealogical notes of animals in the hands

3

of the most prominent breeders. In this way the world's first herd book (the Coates Herd-book) for the Shorthorn or Durham breed was started in 1822, and Eyton's book for the Hereford in 1846. Soon this responsibility was assumed by the breeder associations. On some occasions there were several books belonging to different associations. For example, for the Holstein (Holando) in the USA, a registration association was formed in 1871 and another in 1877. Associations were generally joined together, as they did in 1885. At other times, a single primitive registration was formed. they originated two new ones that continued ahead as representatives of different races. This was the case with the Scottish Black Mocho Cattle book, begun in 1862, which included the ancestors of both the Aberdeen Angus and the Galloway.

FORMATION OF NEW RACES

The exploitation of new regions of the world or the increase of production in certain areas little exploited in the past, created opportunities for new types of animals. In the 20th century, much progress has been made in this regard, with the formation of new bovine breeds: Santa Gertrudis, Indú Brasil, Beefmaster, Brangus, Beefa-lo, etc., created for specific geographic regions and with strict selection on their productive capacity. .

In the formation of all these new races, the process has had some similar aspects, based on crossing:

1) Crossing of a race or blood line that possesses desirable qualities with another race or blood line that possesses other different desirable qualities. Bear in mind that in this century genetics is already a science, and geneticists and not just farmers acted in the formation of these breeds.

2) Exploration of the possible recombinations between the two lines, keeping the individuals that are closest to the desired ideal. Here, the segregation that occurs in F2 and F3 is used, or retro crosses to one of the breeds, ensuring that the animals that enter the retro cross carry some of the qualities that the original breed does not possess.

3) Strict selection of the founding individuals and consequent increase in the consanguinity and uniformity of the founding nuclei.

4) Expansion of the number of individuals of the new breed and the number of breeders dedicated to it. Reduction in the rate of increase in inbreeding and in the selection pressure in less skilled hands than that of the first breeders of the breed.

BIBLIOGRAFIA

Cole, H.H. 1964. Producción Animal. Acribia, Zaragoza.

De Alba, J. 1964. Reproducción y genética animal. IICA, Turrialba, Costa Rica.

Fraser, A. 1970. Criadores y técnicos. Eudeba, Bs.As.

Johansson, I. y Rendel, J. 1971. Genética y mejora animal. Acribia, Zaragoza.

Lush, J.L. 1969. Bases para la selección animal. Ed. Agrop. Peri, Bs.As.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario